Change of Direction Speed Drill Adaptation

by Developing Agility and Quickness, Second Edition: pp. 134 – 136

Kinetic Select

May 2019

This book excerpt is from Developing Agility and Quickness, Second Edition and goes over change of direction drills to help with speed and power development as well as an athletes cognitive and decision making skills.

In Developing Agility and Quickness, Second Edition, leading experts from the NSCA offer more than 130 drills, 12 agility and quickness tests, and 15 sport-specific training plans to help athletes gain a step on the competition.

After athletes become proficient at performing basic COD speed drills, they are ready to progress to those that are more chaotic and unpredictable, similar to what they will experience in their sports. With a few small adaptations, virtually any COD speed drill can be modified to enhance an athlete’s cognitive and decision-making skills. The following are examples of ways to progress many of the COD speed drills in chapter 6 to be reactive (quickness) drills by incorporating temporal (time), spatial (space), and universal (both temporal and spatial) constraints. This can be done by adding a variety of auditory, visual, and mixed cues to COD speed drills.

Auditory cues. The coach may periodically give an auditory (sound), cue, such as switch, change, or stop, while the athlete is performing the drill. At this cue, the athlete should immediately and accurately respond to the coach’s command. For instance, while an athlete is running forward, the coach gives the back command. The athlete responds by immediately decelerating and backpedaling toward the starting line. Additional auditory cues and distracters (i.e., information in which no response is warranted) may be added to agility drills to help the athlete focus on task-relevant auditory information. For example, a football coach might use a snap count to signal the beginning of a drill. Keep in mind that reaction time is typically delayed when more auditory cues are added, because the athletes must decipher among and respond to multiple stimuli. For this reason, coaches should limit possible response cues and distracters to two or three options.

Visual cues. During competition, athletes must constantly scan the field for teammates, opponents, a ball or puck, a referee, or a coach’s signals from the sidelines. For this reason, incorporating different types of visual stimuli and cues may help athletes identify task-relevant game cues more quickly during competition. These cues may be as simple as a coach or teammate pointing to a marker to prompt an immediate change in direction or a signal for the athlete to sprint forward and catch a dropped ball. They may also be as complex as reading an opponent’s movements and responding accordingly.

Mixed cues. Both auditory and visual cues may be combined to challenge even the most advanced athletes. For example, a football athlete randomly tosses a ball to the right or left side of a teammate running forward. As soon as the runner catches the ball, the coach calls out a number between 1 and 3. Each number corresponds to a cone. After catching the ball, the athlete runs to the specified cone to complete the drill. Initially, the runner must visually track the trajectory of the ball in order to receive it. Next, the athlete must listen for the coach’s auditory cue to know where to run to complete the drill or play.

By including these different types of stimuli within basic COD speed drills the athlete can start developing the targeted reactionary skills needed to enhance on-field performance. As with any drill, the more contextually specific it is, the greater the likelihood the athlete will be able to apply it in a game or practice situation. For example, there are numerous products that use light systems that provide a generic reactionary stimulus for athletes to respond to. Typically, these systems have several displays that will randomly light up, signaling the athlete to respond in a certain way. These types of systems may help an athlete develop general reactionary and visual skills, but since they do not provide a contextually specific stimulus (e.g., movement of other players or ball movement) their transferability to competitive situations is questionable (5, 6, 10). Once athletes consistently demonstrate good body control and technique, they can use these drills in a comprehensive agility-training program to improve their reaction time. This sort of program may help athletes perform sport-specific tasks during competition more quickly because they have developed better visual search patterns, anticipation, and speed of recognition (2, 8, 9).

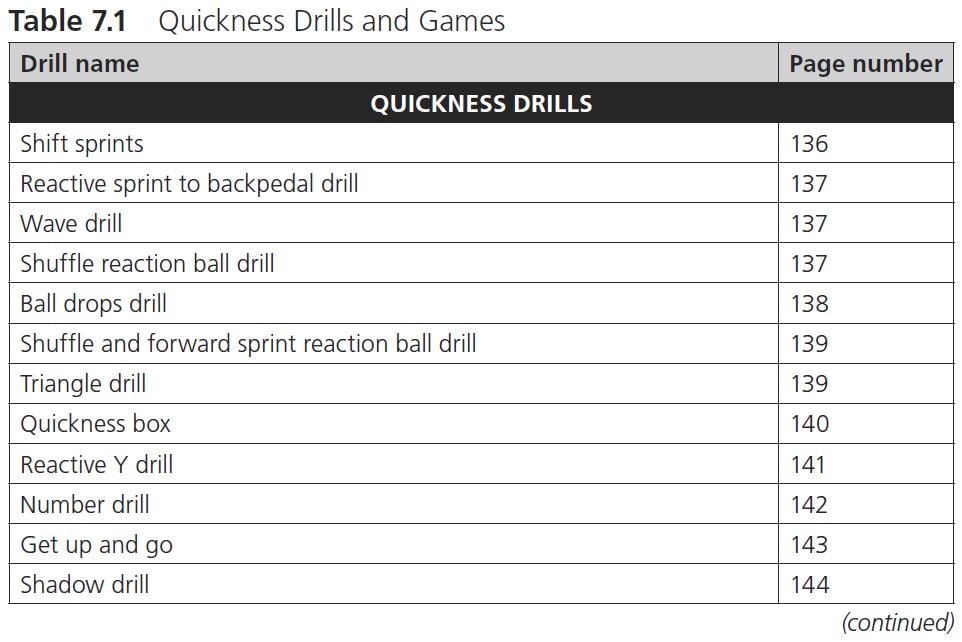

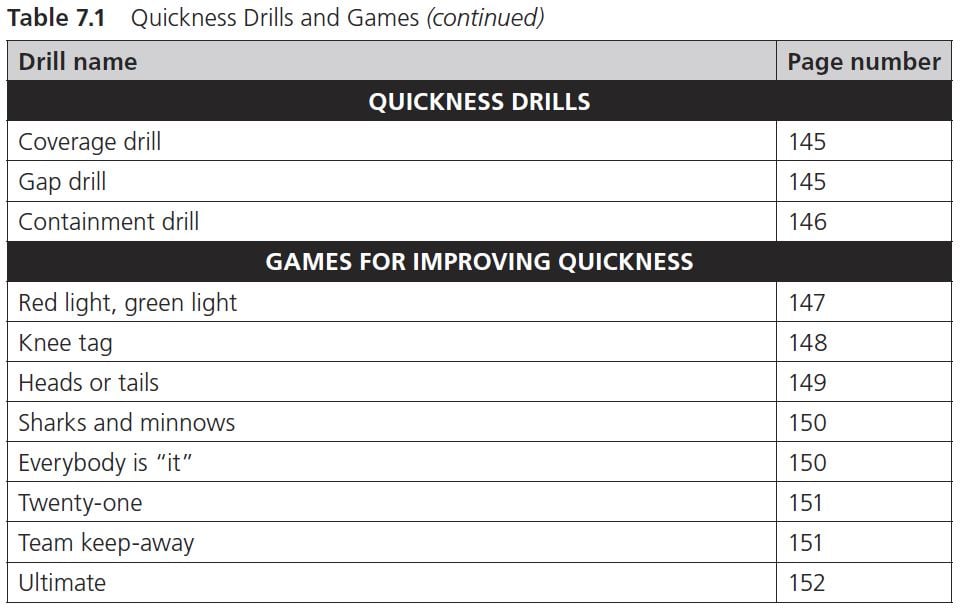

Table 7.1 provides a list of the quickness drills and games included in this chapter.

The book is available in bookstores everywhere, as well as online at the NSCA Store.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Retraction and Correction Policy

- © 2025 National Strength and Conditioning Association