Using Feedback Drills to Coach the Turkish Get-Up

by Manny Romero, CSCS, TSAC-F and Joshua B. Hockett, MS, CSCS,*D, NSCA-CPT,*D, TSAC-F,*D

Personal Training Quarterly

July 2019

Vol 6, Issue 1

This article is an overview of the Turkish get-up movement, as well as cues and drills to help in this movement.

The Turkish get-up (TGU) is a multi-joint exercise designed to improve muscle coordination using fundamental movement patterns, while under load (1). The TGU can be included in a variety of training programs for multiple populations, such as corporate wellness, baseball, football, military, law enforcement, etc. Moreover, the TGU can be used as a therapeutic exercise to improve shoulder and scapular stability, and to help prevent or rehabilitate overuse injuries experienced by repetitive overhead movements (i.e., pitchers, quarterbacks, volleyball players, etc.) (1,2,4). There are several approaches to coaching the TGU; however, the main purpose of this article is to focus on two drills to help guide the learning process for individuals or to use as regressions to reinforce proper kinematic sequencing.

Pattern-Assisted Drill

The first drill will attempt to improve the motor learning experience. The movement pattern is the same as a standard TGU, with the difference being that the load (i.e., resistance band or tubing) assists the user, as opposed to providing resistance to the movement. In this case, the resistance will be used to teach the client how to create stability at the shoulder, and postural integrity throughout the movement. The return phase of this drill seeks to improve eccentric loading in a safe manner; if load is lost, the resistance goes up towards the ceiling instead of down towards the ground. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, no article has been published on this specific exercise.

How to Perform the Pattern-Assisted Drill

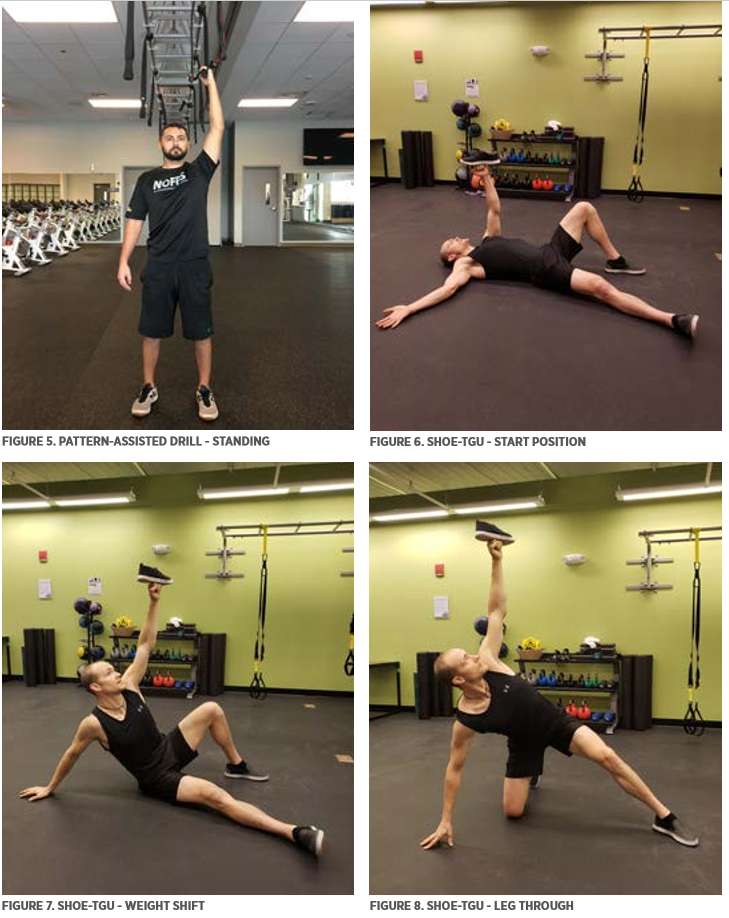

Begin the exercise lying supine with a resistance tube, or similar device, in one hand (Figure 1). Slide the loaded-side scapula back into a stable position and shift the weight towards the opposing hip and elbow in a diagonal rolling motion (Figure 2). Press the forearm into the ground and position the hand flat on the ground. Press the hand into the ground, raise the hips into a high-bridge position, and sweep the bottom leg underneath the body until the knee is directly under the hip to create a partial half-kneeling position (Figure 3). Raise the hand off the ground until the shoulders are directly over the hips, completing the half-kneeling position (Figure 4). Next, shift the hips forward a few inches to gain the necessary leverage to step up into a full-standing position (Figure 5). Lastly, reverse the movement steps to complete the TGU sequence.

Movement Analysis

As the client works through the ascending portion of the TGU (from the ground to standing), the resistance will help to position the body into proper alignment and stimulates the intrinsic muscles needed for postural and scapular stability—more specifically the musculature within the spiral, functional, and deep back arm line (5). If the client is uncertain that his or her scapula has lost the ideal position for stability (retracted and depressed), they can relax the working musculature and reset their scapular position, thus creating feedback to help improve basic motor control. When using compressive loads, the client will not have this luxury. As the client gets closer to the standing phase of the TGU (and because the resistance is essentially gone), they are required to keep the scapula back and down under their own power. When at the fully upright position, the client is now responsible for taking ownership of their kinesthetic awareness. As they begin to descend (return to the starting position), the client will immediately realize the increasing tension from the band, and increasing demands to maintain scapular stability. This will help build the required strength to safely return to the ground without the risk of a weight falling out of the client’s hand—in this case, if the client loses their grip, the resistance goes up.

Unloaded Feedback Drill (Shoe TGU)

The shoe-TGU is another training tool that the strength and conditioning professional can use to assist in learning the efficient movement patterns needed to perform a biomechanically sound and safe TGU (Figures 6 – 10). The shoe-TGU is often used as an introduction to any kind of loaded TGU exercise. Similar to more advanced (loaded) TGU exercises, a strong reinforcement of the importance of strict principles of biomechanics via relationships between center of gravity (COG) and base of support (BOS) are instilled. Unique to this version, however, is that with no firm grip on an implement load (e.g., dumbbell or kettlebell), a shoe is only resting on top of the fist. With the shoe being lightweight and placed at the furthest distance away from the COG, it mimics the position and gravitational forces in the same fashion without any true additional load. Too rapid a perturbation and the shoe will fall off of the fist; therefore, the individual must use careful timing and fluid movements while using global dynamic muscle stabilization throughout the body from foot to fist to keep the shoe COG within the body’s BOS. This pattern then reinforces where a higher load implement needs to be kept to assure optimal loading and positioning.

Sets, Repetitions, and Progressions

Multiple sets (2 – 3) of the pattern-assisted and shoe-TGU drills should be used to promote further strength gains and neuromuscular control (3). Moreover, use of a repetition range (12 or more) and rest period (30 s or less) within the parameters of muscular endurance training is suggested to promote baseline strength and conditioning (3). For trained clients and elite athletes capable of doing multiple sets of 12 or more continuous repetitions with 30 s or less of rest and sound technique, the strength and conditioning professional could consider the use of the traditional TGU, with higher loads of resistance, reduced repetitions and sets, and longer rest periods (3). When introducing resistance, a conservative yet effective approach is the two-for-two rule: if the individual can perform two additional repetitions over their repetition goal during the last set for two consecutive workouts, then weight should be added to the subsequent training session (3). If the athlete cannot perform a complete repetition in ascending and descending form, from the ground and back, the athlete should not progress to higher loads until able to do so with both sides.

Practical Applications

These drills provide the client with feedback for self-correction and understanding the proper movement sequence needed to perform the TGU safely when under compressive loads. These drills can be used to simplify the TGU teaching process in large groups, allowing clients to feel what is right while the strength and conditioning professional provides verbal feedback, and visually monitors the group in an attempt to correct form. Moreover, these drills can be used as a warm-up for experienced practitioners, and could potentially serve as an alternative for those who need to reduce volume after an intense period of training because of the minimal amount of resistance used, and greater demand for safe fundamental movement.

“These drills provide the client with feedback for self-correction and understanding the proper movement sequence needed to perform the TGU safely when under compressive loads.”

Tweet this quote

This article originally appeared in Personal Training Quarterly (PTQ)—a quarterly publication for NSCA Members designed specifically for the personal trainer. Discover easy-to-read, research-based articles that take your training knowledge further with Nutrition, Programming, and Personal Business Development columns in each quarterly, electronic issue. Read more articles from PTQ »

Related Reading

References

1. Ayash, A, and Jones, M. Kettlebell Turkish get-up: Training tool for injury prevention and performance enhancement. International Journal of Athletic Therapy and Training 17(4): 8-13, 2012.

2. Crawford, M. Kettlebells: Powerful, effective exercise and rehabilitation tool. Journal of American Chiropractic Association 48: 7-10, 2011.

3. Haff, GG, and Triplett, NT. Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning, 4th ed. NSCA. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 457-468, 2016.

4. Liebenson, C, and Shaughness, G. The Turkish get-up. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies 15: 125-127, 2011.

5. Myers, TW. Anatomy Trains: Myofascial Meridians for Movement and Manual Therapists (3rd ed). Churchill Livingston; 2014.

6. Shinkle, J, Nesser, TW, Demchak, TJ, and McMannus, DM. Effect of core strength on the measure of power in the extremities. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 26(2): 373-380, 2012.

- Privacy Policy

- Your Privacy Choices

- Terms of Use

- Retraction and Correction Policy

- © 2025 National Strength and Conditioning Association